Priority sites in the high seas

We work to secure lasting protection for biodiversity hotspots in our shared ocean.

High seas conservation sites

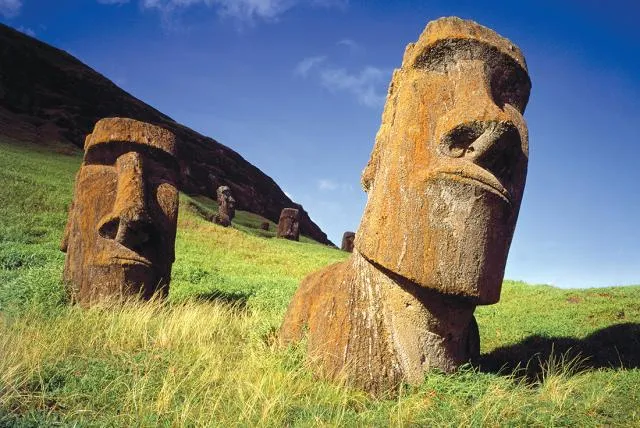

Salas y Gómez and Nazca Ridges

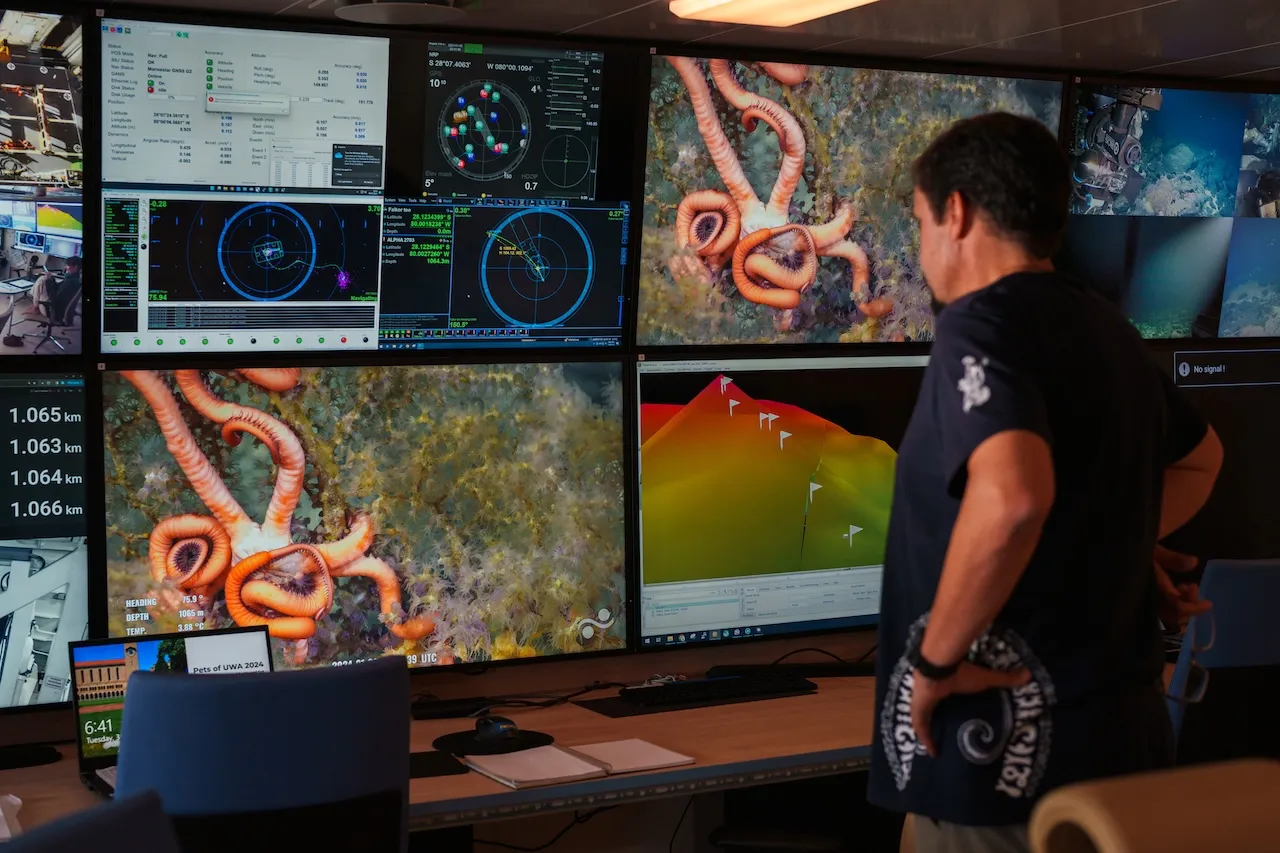

Stretching nearly 3,000 kilometers from Rapa Nui to the shores of South America, the Salas y Gómez and Nazca ridges are underwater mountain chains teeming with coral reefs.

Recognized as an Ecologically or Biologically Significant Area (EBSA) by the Convention on Biological Diversity, these ridges are among the most ecologically rich places on Earth.

The pathway to protection

More than 70% of the Salas y Gómez and Nazca ridges lie beyond national jurisdiction without legal protection.

We are working on the development of a marine protected area proposal, coordinating national, regional, and international workshops, while building regional ownership and fisheries management through South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organization (SPRFMO).

Regional MPA workshop - March 2026

Hosted after the SPRFMO Commission in Panama, the Government of Chile in partnership with Coral Reefs of the High Seas will convene regional stakeholders to advance the Salas y Gómez and Nazca ridges BBNJ MPA proposal.

Scientific committee meeting - September 2026

The SPRFMO Scientific Committee meets in the Faroe Islands, with the goal of agreeing on enhanced fisheries management measures.

International MPA workshop - November 2026

Experts convene to refine and advance the high seas MPA proposal.

BBNJ Conference of Parties - 2026-2027

The first milestone BBNJ CoPs are held as the Salas y Gómez and Nazca BBNJ MPA proposal progresses, positioned to be formally submitted at the second CoP.

What we aim to achieve

Our goal is to achieve lasting protection for the Salas y Gómez and Nazca ridges by combining fisheries management measures under the South Pacific RFMO with a high seas MPA designation under the BBNJ Agreement.

Together, these strategies form a unified pathway to conserve biodiversity, maintain ecosystem integrity, and create a durable governance model for one of the most unique and vulnerable marine regions on the planet.

Why protection matters

Biodiversity

The Salas y Gómez and Nazca ridges are home to over 90 species at risk of extinction - including sharks, seabirds, whales, turtles, and corals. They host the highest recorded levels of marine endemism, with species found nowhere else on Earth.

Livelihoods

These underwater peaks provide crucial breeding and nursery grounds for ocean life, including commercially important jack mackerel and Humboldt giant flying squid, which underpin coastal livelihoods.

Culture and history

Human history is imprinted on the ridges which served as a voyaging route for Polynesian explorers – people intimately connected with the ocean. Indigenous Pacific Islanders have long recognized the importance of these waters.

Rapa Nui hakanononga sites mark productive fishing spots above seamounts, evidence of centuries of deep knowledge and stewardship.

%20-%20Daniel%20Wagner%2C%20Conservation%20International..webp)

Threats and urgency

Commercial activity in the region is still low, but pressures are mounting from overfishing, pollution, climate change, and deep-sea mining interests. While Peru and Chile have protected waters within their national jurisdictions, over 70% of the ecosystem lies in areas beyond national control and remains unprotected.

This extraordinary ecosystem continues to yield new discoveries and its protection is urgent.

Featured resource

The Case for Conservation of the Salas y Gómez and Nazca Ridges

Saya de Malha

Hidden in the high seas between Mauritius and Seychelles, Saya de Malha is a vast underwater forest of seagrass, stretching across 40,000 km².

One of the world’s largest seagrass meadows and most powerful carbon sinks, it supports rich coral reefs, migratory species, and unique endemic life. Despite its global significance, this remote ocean paradise is one of the least explored places on Earth.

What we aim to achieve

Saya de Malha sits on the Mascarene Plateau and within the Joint Management Area jointly managed by Seychelles and Mauritius, providing a rare legal foundation for cooperation. Combined with the BBNJ Agreement, this creates a unique opportunity to achieve protection now.

Building on our experience in the Salas y Gómez and Nazca ridges, the Coalition will apply a science-led, inclusive approach, working with regional partners to deliver lasting protection for Saya de Malha.

Why protection matters

Biodiversity

Saya de Malha is the largest underwater bank in the world, shallow and home to abundant marine life. From deep-sea fish and pelagic predators to extensive coral communities, it’s one of the most biologically rich areas of the high seas.

Livelihoods

Its sprawling seagrass meadows and nursery grounds sustain regional fisheries, supporting the food security and livelihoods of Mauritius, Seychelles, and neighboring islands.

Climate

Globally, seagrass meadows capture vast amounts of blue carbon - around 20% of oceanic carbon. The Saya de Malha is a powerful natural ally in climate regulation and resilience.

Threats and urgency

Saya de Malha’s isolation has kept it pristine, but its future is at risk. Industrial and illegal fishing, oil and gas exploration, and looming seabed mining are closing in.

Without urgent protection, this globally vital ecosystem could face irreversible damage.